Concurrency or Parallelism ?

First of all, You need to know Go is a concurrent language and not a parallel one. Before discussing how concurrency is taken care in Go, we must first understand what is concurrency and how it is different from parallelism.

What is concurrency?

Concurrency is the capability to deal with lots of things at once. It's best explained with an example.

Let's consider a person jogging. During his morning jog, let's say his shoelaces become untied. Now the person stops running, ties his shoelaces and then starts running again. This is a classic example of concurrency. The person is capable of handling both running and tying shoelaces, that is the person is able to deal with lots of things at once 😃

What is parallelism and how is it different from concurrency?

Parallelism is doing lots of things at the same time. It might sound similar to concurrency but it's actually different.

Let's understand it better with the same jogging example. In this case, let's assume that the person is jogging and also listening to music on his iPod. In this case, the person is jogging and listening to music at the same time, that is he is doing lots of things at the same time. This is called parallelism.

Concurrency and Parallelism - A technical point of view

We understood what is concurrency and how it is different from parallelism using real world examples. Now let's look at them from a more technical point of view as we are geeks 😃.

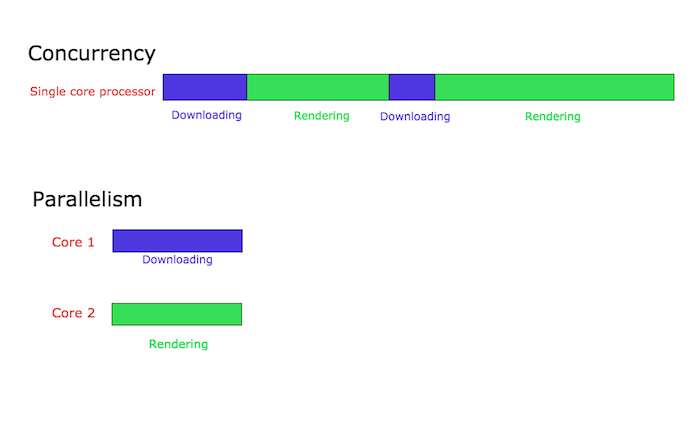

Let's say we are programming a web browser. The web browser has various components. Two of them are the web page rendering area and the downloader for downloading files from the internet. Let's assume that we have structured our browser's code in such a way that each of these components can be executed independently (This is done using threads in languages such as Java and in Go we can achieve this using Goroutine, more on this later). When this browser is run in a single-core processor, the processor will context switch between the two components of the browser. It might be downloading a file for some time and then it might switch to render the html of a user requested web page. This is known as concurrency. Concurrent processes start at different points of time and their execution cycles overlap. In this case, the downloading and the rendering start at different points in time and their executions overlap.

Let's say the same browser is running on a multi-core processor. In this case, the file downloading component and the HTML rendering component might run simultaneously in different cores. This is known as parallelism.

Parallelism will not always result in faster execution times. This is because the components running in parallel have might have to communicate with each other. For example, in the case of our browser, when the file downloading is complete, this should be communicated to the user, say using a popup. This communication happens between the component responsible for downloading and the component responsible for rendering the user interface. This communication overhead is low in concurrent systems. In the case when components run in parallel in multiple cores, this communication overhead is high. Hence parallel programs do not always result in faster execution times!

Support for concurrency in Go. Concurrency is an inherent part of the Go programming language.

That's it for introduction to concurrency.

Goroutine

What are goroutines?

Goroutines are functions or methods that run concurrently with other functions or methods. Goroutines can be thought of as lightweight threads. The cost of creating a Goroutine is tiny when compared to a thread. Hence it's common for Go applications to have thousands of Goroutines running concurrently.

Let's create a Goroutine.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func hello() {

fmt.Println("Hello world goroutine")

}

func main() {

go hello()

fmt.Println("main")

}

Run this program and you will have a surprise!

This program only outputs the text main function. What happened to the Goroutine we started? We need to understand the two main properties of goroutines to understand why this happens.

- When a new Goroutine is started, the goroutine call returns immediately. Unlike functions, the control does not wait for the Goroutine to finish executing. The control returns immediately to the next line of code after the Goroutine call and any return values from the Goroutine are ignored.

- The main Goroutine should be running for any other Goroutines to run. If the main Goroutine terminates then the program will be terminated and no other Goroutine will run.

I guess now you will be able to understand why our Goroutine did not run. After the call to go hello() , the control returned immediately to the next line of code without waiting for the hello goroutine to finish and printed main. Then the main Goroutine terminated since there is no other code to execute and hence the hello Goroutine did not get a chance to run.

Let's fix this now.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func hello() {

fmt.Println("Hello world goroutine")

}

func main() {

go hello()

time.Sleep(1 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("main")

}

Now run this code. Output is

Hello world goroutine

main

What we do is just add a Millisecond.

This way of using sleep in the main Goroutine to wait for other Goroutines to finish their execution is a hack we are using to understand how Goroutines work. Channels can be used to block the main Goroutine until all other Goroutines finish their execution. We will discuss channels after this.

Starting multiple Goroutines

Run this

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func numbers() {

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

time.Sleep(250 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("%d ", i)

}

}

func alphabets() {

for i := 'a'; i <= 'e'; i++ {

time.Sleep(400 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("%c ", i)

}

}

func main() {

go numbers()

go alphabets()

time.Sleep(3000 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("main terminated")

}

This program output:

1 a 2 3 b 4 c 5 d e main terminated

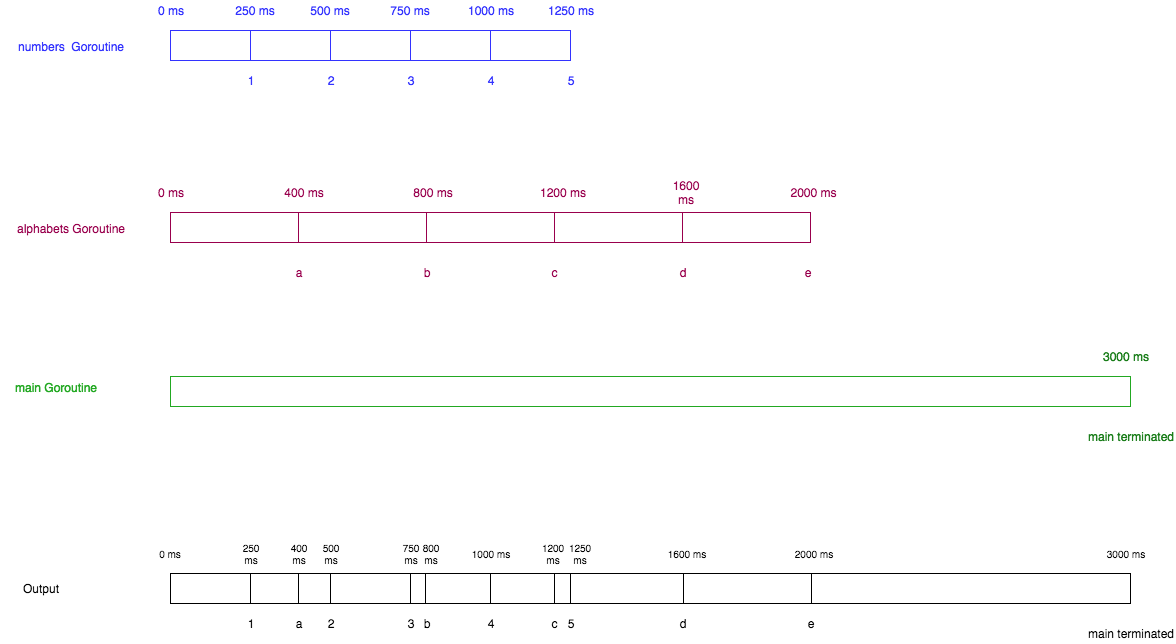

The following image depicts how this program works. Please open the image in a new tab for better visibility 😃

The first portion of the image in blue color represents the numbers Goroutine, the second portion in maroon color represents the alphabets Goroutine, the third portion in green represents the main Goroutine and the final portion in black merges all the above three and shows us how the program works. The strings like 0 ms, 250 ms at the top of each box represent the time in milliseconds and the output is represented in the bottom of each box as 1, 2, 3 and so on. The blue box tells us that 1 is printed after 250 ms, 2 is printed after 500 ms and so on. The bottom of the last black box has values 1 a 2 3 b 4 c 5 d e main terminated which is the output of the program as well. The image is self-explanatory and you will be able to understand how the program works.

Channel

What are channel?

Channels can be thought of as pipes using which Goroutines communicate. Similar to how water flows from one end to another in a pipe, data can be sent from one end and received from the other end using channels.

Declaring channels

Each channel has a type associated with it. This type is the type of data that the channel is allowed to transport. No other type is allowed to be transported using the channel.

chan T is a channel of type T

The zero value of a channel is nil. nil channels are not of any use and hence the channel has to be defined using make similar to maps and slices.

Let's write some code that declares a channel.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a chan int

if a == nil {

fmt.Println("channel a is nil, going to define it")

a = make(chan int)

fmt.Printf("Type of a is %T", a)

}

}

Outputs:

channel a is nil, going to define it

Type of a is chan int

As usual, the short hand declaration is also a valid and concise way to define a channel.

a := make(chan int)

The above line of code also defines an int channel a.

Sending and receiving from a channel

a <- data // write to channel a

data := <- a // read from channel a

Nothing to explain.

Sends and receives are blocking by default

Sends and receives to a channel are blocking by default. What does this mean? When data is sent to a channel, the control is blocked in the send statement until some other Goroutine reads from that channel. Similarly, when data is read from a channel, the read is blocked until some Goroutine writes data to that channel.

This property of channels is what helps Goroutines communicate effectively without the use of explicit locks or conditional variables that are quite common in other programming languages.

It's ok if this doesn't make sense now. The upcoming sections will add more clarity on how channels are blocking by default.

Channel example program

We will rewrite the above program using channels.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func hello(done chan bool) {

fmt.Println("Hello world goroutine")

done <- true

}

func main() {

done := make(chan bool)

go hello(done)

<-done

fmt.Println("main")

}

In the above program, we create a done bool channel in line no. 12 and pass it as a parameter to the hello Goroutine. In line no. 14 we are receiving data from the done channel. This line of code is blocking which means that until some Goroutine writes data to the done channel, the control will not move to the next line of code. Hence this eliminates the need for the time.Sleep which was present in the original program to prevent the main Goroutine from exiting.

The line of code <-done receives data from the done channel but does not use or store that data in any variable. This is perfectly legal.

Now we have our main Goroutine blocked waiting for data on the done channel. The hello Goroutine receives this channel as a parameter, prints Hello world goroutine and then writes to the done channel. When this write is complete, the main Goroutine receives the data from the done channel, it is unblocked and then the text main function is printed.

This program outputs

Hello world goroutine

main

Let's modify this program by introducing a sleep in the hello Goroutine to better understanding this blocking concept.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func hello(done chan bool) {

fmt.Println("hello go routine is going to sleep")

time.Sleep(4 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("hello go routine awake and going to write to done")

done <- true

}

func main() {

done := make(chan bool)

fmt.Println("Main going to call hello go goroutine")

go hello(done)

<-done

fmt.Println("Main received data")

}

In the above program, we have introduced a sleep of 4 seconds to the hello function in line no. 10.

This program will first print Main going to call hello go goroutine. Then the hello Goroutine will be started and it will print hello go routine is going to sleep. After this is printed, the hello Goroutine will sleep for 4 seconds and during this time main Goroutine will be blocked since it is waiting for data from the done channel in line no. 18 <-done. After 4 seconds hello go routine awake and going to write to done will be printed followed by Main received data.

Deadlock

One important factor to consider while using channels is deadlock. If a Goroutine is sending data on a channel, then it is expected that some other Goroutine should be receiving the data. If this does not happen, then the program will panic at runtime with Deadlock.

Similarly, if a Goroutine is waiting to receive data from a channel, then some other Goroutine is expected to write data on that channel, else the program will panic.

package main

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

ch <- 5

}

In the program above, a channel ch is created and we send 5 to the channel in line no. 6 ch <- 5. In this program no other Goroutine is receiving data from the channel ch. Hence this program will panic with the following runtime error.

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

main.go:6 +0x31

exit status 2

Unidirectional channels

All the channels we discussed so far are bidirectional channels, that is data can be both sent and received on them. It is also possible to create unidirectional channels, that is channels that only send or receive data.

package main

import "fmt"

func sendData(sendch chan<- int) {

sendch <- 10

}

func main() {

sendch := make(chan<- int)

go sendData(sendch)

fmt.Println(<-sendch)

}

In the above program, we create send only channel sendch in line no. 10. chan<- int denotes a send only channel as the arrow is pointing to chan. We try to receive data from a send only channel in line no. 12. This is not allowed and when the program is run, the compiler will complain stating,

./main.go:12:14: invalid operation: <-sendch (receive from send-only type chan<- int)

All is well but what is the point of writing to a send only channel if it cannot be read from!

This is where channel conversion comes into use. It is possible to convert a bidirectional channel to a send only or receive only channel but not the vice versa.

package main

import "fmt"

func sendData(sendch chan<- int) {

sendch <- 10

}

func main() {

chnl := make(chan int)

go sendData(chnl)

fmt.Println(<-chnl)

}

In line no. 10 of the program above, a bidirectional channel chnl is created. It is passed as a parameter to the sendData Goroutine in line no. 11. The sendData function converts this channel to a send only channel in line no. 5 in the parameter sendch chan<- int. So now the channel is send only inside the sendData Goroutine but it's bidirectional in the main Goroutine. This program will print 10 as the output.

Closing channels and for range loops on channels

Senders have the ability to close the channel to notify receivers that no more data will be sent on the channel.

Receivers can use an additional variable while receiving data from the channel to check whether the channel has been closed.

v, ok := <- ch

In the above statement ok is true if the value was received by a successful send operation to a channel. If ok is false it means that we are reading from a closed channel. The value read from a closed channel will be the zero value of the channel's type. For example, if the channel is an int channel, then the value received from a closed channel will be 0.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func producer(chnl chan int) {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

chnl <- i

}

close(chnl)

}

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go producer(ch)

for {

v, ok := <-ch

if ok == false {

break

}

fmt.Println("Received ", v, ok)

}

}

Outputs:

Received 0 true

Received 1 true

Received 2 true

Received 3 true

Received 4 true

Received 5 true

Received 6 true

Received 7 true

Received 8 true

Received 9 true

The for range form of the for loop can be used to receive values from a channel until it is closed.

Let's rewrite the program above using a for range loop.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func producer(chnl chan int) {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

chnl <- i

}

close(chnl)

}

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go producer(ch)

for v := range ch {

fmt.Println("Received ",v)

}

}

The for range loop in line no. 16 receives data from the ch channel until it is closed. Once ch is closed, the loop automatically exits. This program outputs,

Received 0

Received 1

Received 2

Received 3

Received 4

Received 5

Received 6

Received 7

Received 8

Received 9

Congratulations on completing this tutorial, and welcome to continue learning in practice.